Today marks the centenary of the birth of

Anthony Powell, one of my favorite authors. He occupies the top deck of the old E.P. pantheon—alongside Charles Portis and maybe that Nabokov fellow.

For several years now I've wanted to write something* about Powell; this year would have been the one to do it, but such an undertaking would require, at the very least, another pass through his very long novel,

A Dance to the Music of Time, which appeared in 12 volumes from 1951 to 1975. More recently (over the past two years), there's been an AP biography by Michael Barber (savaged by the U.K. press), which I thought was helpful for the non-Anglophile reader (i.e., myself); a reissue of Hilary Spurling's

Invitation to the Dance, a guide to the characters and places woven throughout

ADTTMOT; reissues of his two final, non-Dance-related comic novels,

O, How the Wheel Becomes It! (Green Integer) and

The Fisher King (Chicago), both of which I recommend—The Fisher King in particular; and

Understanding Anthony Powell, an academic treatment of Powell's works.

This piece in the

Scotsman is a generally sound assessment, though a bit dry for my taste—Powell is a very funny writer, and I don't think this comes through. Constant comparisons of Powell to Proust make

ADTTMOT seem daunting, but I think almost anyone would enjoy dipping his/her toe/toes into one of Powell's very funny early novels, ideally

Afternoon Men (1931). (

Venusberg,

What's Become of Waring, and

Agents and Patients are also worthwhile; I haven't read

From a View to a Death yet—saving it for my old age.) (Speaking of which: Powell lived until March 2000—he was 94 years old.)

The

Scotsman article asserts that "Powell, though an inferior writer to Waugh, was the best chronicler of the British 'establishment' over most of the 20th century." Inferior? I'm not so sure. I've read and liked some Waugh, but I maintain that Powell's the more satisfying writer. There's a difference in tone and scope; still, it's not unhelpful to think of Powell as some mix of Waugh and Proust.

After making that formulation, throw it away!

* * *

There's much more I want to say about Powell in this space. For now, I'll just relate how it was on a family trip to Yellowstone (c. 1997) that, browsing in a haphazardly organized bookstore in Montana, I came across

Afternoon Men. I'd heard of Powell and the

Dance, and was attracted to the book's title and epigraph—derived from Burton's

The Anatomy of Melancholy, which I was already fairly obsessed with. If I hadn't gone into that store...seen that book at

that moment...if the store hadn't been so otherwise humdrum (i.e., there weren't really any other titles of interest)...would I have read Powell, adored him, let him into my life to this extent?

I say "Powell," as if referring to the person rather than the work—that might be apt, given the nature of the

Dance. Aside from the page-by-page pleasures, the grander—the "macro"—satisfaction is in how certain characters weave in and out of the narrator's life, disappearing for volumes at a time, having offstage lives of their own. As enjoyable as his short, single-volume novels are, Powell is unparalleled in this sort of overarching view of life, an effect** only achievable over the course of a very long book.

That's

really enough for now!

---------

*I.e., something grand; I've written

smallish things and glancing references.

**"Effect" sounds cold; rest assured that the scale is always human, always accessible. His long chapters (c. 50-70 pages) are typically accounts of the events of a rather small unit of time, often a party of some sort. His magic is in imbuing all the banter, the gossip, the parade of personalities with considerable import, a quality that may not be apparent until the chapter or book is over.

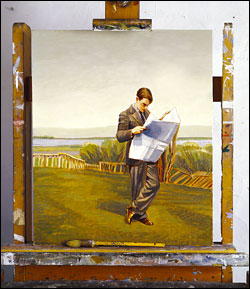

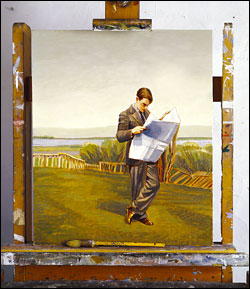

Note: the painting and photo of the painting are by Duncan Hannah. To read more about the story behind this image, go

here.